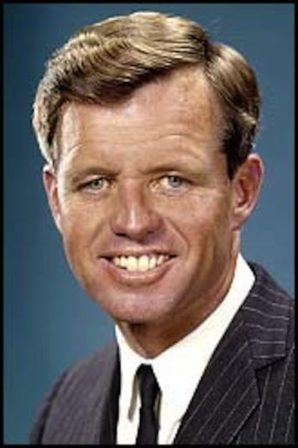

Remembering Bobby

By

George Mitrovich

On Saturday, 16 March 1968, Robert F. Kennedy announced he was running for president of the United States.

“Each time a man stands up for an ideal, or acts to improve the lot of others, or strikes out against injustice, he sends forth a tiny ripple of hope, and crossing each other from a million different centers of energy and daring those ripples build a current which can sweep down the mightiest walls of oppression and resistance.”— Robert F. Kennedy Cape Town, South Africa 6 June 1966

This is a column I didn’t want to write, not wishing to relive the searing memories of 50 years ago when Bobby Kennedy lay mortally wounded on the kitchen floor of the Ambassador Hotel in Los Angeles.

But Robert F. Kennedy in life and in death changed my life, so that is why I write:

On Saturday, 16 March 1968, Robert F. Kennedy announced he was running for president of the United States. In that speech the senator said:

“I do not run for the presidency merely to oppose any man but to propose new policies. I run because I am convinced that this country is on a perilous course and because I have such strong feelings about what must be done, and I feel that I’m obliged to do all that I can…”

Watching on televisions at our home in Whittier, I knew I wanted to be a part of his campaign; I knew it would be a presidential campaign unlike any other – the chance to raise again America’s collective consciousness on issues of social justice; that in Bobby Kennedy we might comprehend the truth of what Camus wrote, “I should like to be able to love my country and still love justice.”

Through the help of Pierre Salinger, who had been President Kennedy’s press secretary, I was hired by Bobby’s campaign and sent in late March to Omaha, Nebraska, a then critical primary state.

Upon arrival I went to the Sheraton Fontanelle Hotel, headquarters for the campaign, where I met Steve Smith, the legendary Kennedy brother-in-law, and overseer of the family’s business interests.

For someone like me, a 33-year old unknown from California, meeting Smith was a big deal. Like many others Kennedy and Camelot had captivated me. I had read extensively about the family and followed closely stories on radio and television about President Kennedy and his administration, which had created an excitement about politics and the possibilities of government missing in the Eisenhower years.

Like most Americans, save for the hate mongering fringe, I was devastated by the president’s death; the 1,000 days of his presidency had brought hope and a sense of renewal to the American spirit, but now it was over, ended by his assassination in Dallas.

But five years later I found a sense of hope reborn by Bobby and what forcibly struck me as his moral commitment to politics.

I first met Bobby late on a Friday night at the Hilton Hotel in downtown Denver. He had spent the day campaigning with Caesar Chavez in California’s Central Valley before flying east to Colorado. He was leaning against a wall in his suite. He was wearing a blue nightshirt. He looked absolutely beat.

Frank Mankiewicz, his press secretary and former Latin American director for the Peace Corps, introduced me, but I’m not sure it registered, because Bobby fixed me with a quizzical look of, “Who are you?” But Frank said, pay no attention, the senator was extremely tired.

(Mankiewicz would thereafter become my political mentor in all things media. It was he who first said to me, “If you can’t tell the press the truth then tell them nothing at all.” A charge I have faithfully observed these 50 years.)

The next morning early while the campaign entourage and press waited, Bobby went off for a brisk walk with his dog, a cocker spaniel named Freckles. We then went to the Denver airport to board a chartered American Airlines Lockheed Electra; we were bound for Scottsbluff, a small Nebraska town near the Wyoming border.

During the flight I was surprised when one of the senator’s secretaries told me he wanted me to join him for breakfast. No, really, that was a surprise. After all I was just one press aide among many in the campaign. But Bobby wanted to know my “take” on Nebraska, What was going on? How did it look? What were our chances? Sitting opposite of him with a small table between us, between bites of breakfast and sips of coffee, I realized that when he spoke, he spoke directly to you and to no one else. He had an ability to lock in on you, to make you think you just might be the most important person in his campaign.

That day across the northern tier of Nebraska, proved exhausting, before finally ending late at the airport in Norfolk, in the middle of the state.

The American charter was waiting to take Bobby to McLean, Virginia, as he sought to be home on Sundays with his family. Before boarding the plane people said their goodbyes to the senator. When my turn came I told him to make sure he got some rest. He looked at me and said, “God yes, I need it.” He started up the steps to the plane, but stopped. He came back down and walked over to me. He took my hand and said, “Thank you for today. It was very well done.”

It was, to be sure, a small moment, but sometimes in this life character is measured by such small moments; sometimes such acts reveal depths of inner decency and kindness; sometimes they tell you that at a person’s core there is caring and respects for others, no matter how great the relative difference in their positions of power and standing; and sometimes such “small” acts separate the ordinary from the extraordinary – and Robert F. Kennedy was extraordinary.

There was another long day of campaigning (a redundancy, they were all long, hard days, this time through the small towns of southeastern Nebraska. At one of the stops along the way, in Beatrice, Bobby went inside a state hospital, a place where hydrocephalic children were being cared for (children with abnormally large heads).

Before he went in, Bill Lawrence of ABC News, asked me if I was coming? I told him I would wait outside, that I wasn’t good in such circumstances. Sometime later Bobby and the press came out of the hospital. What I saw were members of the press in tears.

I asked Lawrence what happened? He said Bobby had taken these hydrocephalic children into his arms, speaking lovingly to them while caressing and kissing their foreheads. It was, Lawrence said, an extraordinarily moving moment – and clearly the press was affected by what they witnessed.

On the day after the Nebraska primary, which Bobby won decisively, we made a quick trip to Detroit, where more than a 100,000 people greeted the senator. We flew back west to Los Angeles. When we arrived at LAX, my wife, La Verle, and our three children, Carolyn, Mark, and Tim, were waiting to greet me, as I had not seen them in several months.

There was a large crowd waiting to see Bobby in the boarding area (this was before security concerns kept people away from such areas). The staff was pushing Bobby to get off our American charter flight, but I asked if he would say hello to my family? He asked, “Where are they?” “Outside in the terminal,” I answered. He told me to bring them on board. It was obvious some staff members were annoyed, but I did as asked. He greeted La Verle, and then asked each of our children their names, ages, and where they went to school. He focused on them — and they remember that moment.

No one can say with certainty what we lost when Bobby died 6 June 1968, but I believe our world would be a vastly different place had he lived – that both America and the world would have been spared so much of the hell the last 50 years has brought — and we might never have heard the name, Donald Trump.

For I am certain Bobby would have been the nominee of the Democratic Party for president in ‘68, and would have defeated Richard Nixon. Two reasons: First, because Mayor Daley and his thugs would not have done to Bobby in Chicago what they did to Eugene McCarthy, and, secondly, Hubert Humphrey, with all the baggage of Vietnam and the Johnson presidency, still lost to Nixon by fewer than 500,000 votes.

Yes, our world would have been vastly different.

But if you know anything about the Kennedys, you would know they do not live in the past. As Ethel Kennedy told NBC’s Tom Brokaw in an interview 25 years after Bobby’s death, “Kennedys do not do would ofs, could ofs, or should ofs.”

And neither should we.

_______________________________________________________________________

George Mitrovich is a San Diego civic leader. He may be reached at, gmitro35@gmail.com.

Category: Featured Articles, Local News, National News