Everything changes and everything stays the same

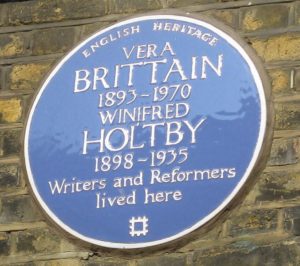

PBS Masterpiece recently aired a three-part adaptation of Winifred Holtby’s 1935 novel, “South Riding.” I knew Holtby as an outspoken feminist and advocate for social justice and as the first biographer of Virginia Woolf, but I’d never read her fiction. “South Riding” was her last novel, published posthumously and considered her greatest work.

The television mini-series was a well-produced drama, but as is often the case with movie and TV adaptations, I felt that a lot was missing. In the interests of time and pizzazz, audience attention and satisfaction, many novels are reduced to their most skeletal elements, the conflicts and the love stories. With any luck the film will remain essentially faithful to the book, but what you see may not be what it’s really about.

There was enough going on to convince me that “South Riding” was a lot more than Sarah Burton’s unrequited love for Robert Carne, so I checked the book out of the library and launched into a fascinating and complex saga. The novel pursues a number of complex and overlapping storylines. The relationship between liberal schoolmistress Sarah and conservative farmer Carne is just one of them.

Above all else, it’s about community and local government—the good, the bad and the ugly. The South Riding of the title is a fictional region, several towns and villages in Yorkshire County on the coast of northern England. The ruling bodies at the time were the municipal and county councils. Holtby’s mother had been a council member, known as aldermen (alderwomen? alderpersons?—no such distinction was thought necessary at the time) in the Yorkshire town where she was raised, so Holtby had a front-seat view. One of the main characters in “South Riding” is Alderman Mrs. Beddows, thought to be modeled after Holtby’s mother, the only woman on the council, a voice of reason and compassion.

The workings of the council—their decisions, impact on various constituencies, greed and self-interest, the bargaining and buying of votes and other shenanigans taking place behind closed doors—are little different from what we see today in all branches of government.

Sarah does tireless battle about needed improvements at her school, about public education in general, about priorities that place profits over people. Newly elected Alderman Joe Astell comes out of London politics and the labor movement; now his focus is on local issues, many of which seem inconsequential. He tells Sarah, “You begin by thinking in terms of world revolution and end by learning to be pleased with a sewage farm.” We come to understand, however, as do many of us who come out of the Civil Rights and Anti-War movements to work in local politics, that it may be possible to have a greater impact on a smaller scale, bringing about changes that will immediate improve people’s lives, rather than striving for global change in one fell swoop.

There’s a tendency to think that a 1930s English novel isn’t going to be relevant. Yet it isn’t much different from the issues we deal with here and now.

Category: Entertainment