My Life in Books & Literature

Twenty years ago, maybe, I spoke on “My Life in Books & Literature.” I gave the speech three times – at Barnes & Noble at Grossmont Center and La Jolla, and to a women’s book club at First United Methodist Church of San Diego.

The first went extremely well. The second, not so much. The third was best.

The outline of my speech was in five parts: the act of reading, the joy of discovery, the arts and reading, writers and reading, and why one should read.

The speech, in outline form, ran 2,500 words long, but I’m not doing that here, as I have no wish to complicate Ms. Brooks’ life as publisher of the Sentinel.

Reading as an act began when I was six or seven, but I wasn’t reading books. I was reading sports pages. I later added magazines and books, but I have never stopped reading sports sections.

But to read as widely as I do, not just about sports, obviously, but about issues that affect our lives in ways infinitely beyond the games men and boys play, you must read selectively, and I do.

A habit forced on me as press secretary to United States Senator Charles Goodell, Republican of New York, as every morning when I came to my desk in the senator’s office, I confronted a big stack of newspapers, from The New York Times to Newsday, from the Buffalo Evening News to the Staten Island Advance, and a great many others, and it was my job, and that of my assistant, Sue Goff, to go through the stack to determine if there was an issue we thought the senator might address.

But that habit has served me well, enabling me to pick and choose stories, columns and articles, I think worthy of people’s time and attention, as anyone would know who is on my Facebook page and a special list of those who receives my postings by email – and I hope is reflected in my monthly columns for the Sentinel.

Which brings me to the joy of discovery, and a wonderful story I found in Nicholas Basbanes, “A Gentler Madness: Bibliophiles, Bibliomanes, and the Eternal Passion for Books,” in which he tells about John Larroquette, the actor:

“A few days before (one of his plays was to open) Larroquette was browsing through a shop in Venice, California, that specialized in sea-shells. “In the back was a little shelf with books on it, and among them was this 16-volume collection of Beckett’s works that Grove Press published in 1970. There was a signed limited set there for $400, which was too much money for Larroquette. The 16 volumes were $125. They weren’t first editions, of course, the actor said, “but they were all of Beckett’s plays. I bit my tongue and paid the money for these books. It gave me such a wonderful feeling that in one fell swoop I had gotten all of these books. It just gave me a feeling of fulfillment.”

My own, more modest joy of discovery involved a used book store on Fifth Avenue in Hillcrest. I was browsing through a section of books about France and came across “My ten Life in Exile,” by Madame de Stael. I did not know Madame de Stael, but would subspecialty learn much about her remarkable life. Indeed, Madame de Stael became one of my heroes.

Ann Louise Germaine Necker de Stael-Holstein was the daughter of Louis XVI’s finance minister, who married a Swedish diplomat, and was a contemporary of Napoleon, for whom she had great contempt.

Of the “Little Corporal from Corsica,” as he was dismissively referred to by his opponents, she would write:

“His face is thin and pale, but not unpleasing. Being short of stature, he looks better on horseback than on foot. In social life, he has rather awkward manners, though he is by no means shy…When he is speaking, I am enthralled by an impression of his pre-eminence, though he has none of the qualities of the men of the study and of society…I have known not a few men of note, some of them savage by disposition, but the dread with which this man fills me is a thing apart. He is neither good nor bad, neither gentle nor cruel. He is unique; he can neither inspire nor feel affection…Character, mind, speech – all have a strange stamp. This very strangeness helps him win over the French.

“He neither hates nor loves; for him, no one exist but himself; all other people are merely ‘number so-and-so.’ A great chess player, for whom humanity-at-large is the adversary he hopes to checkmate. His success is quite as much due to the qualities he lacks as to the qualities he possesses…Where his own interest is involved, he pursues it as a just man seeks virtue; if his aim were good, his perseverance would be exemplary…He despises the nation whose applause he seeks; there is not a spark of fervor-intermingled with his craving to astound mankind…I have never been able to breathe freely in his presence.”

Do her words remind you of someone we know?

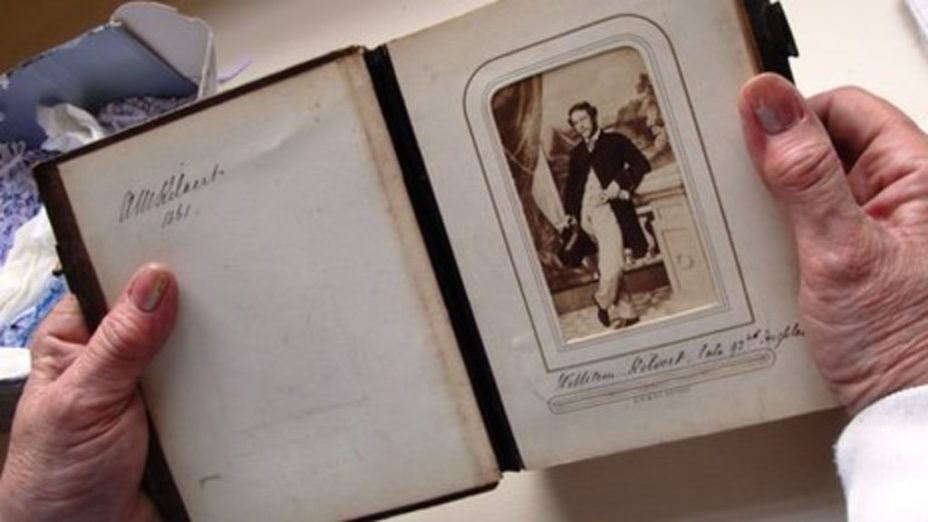

“Francis Kilvert & His Diary” I found among bargain books at Barnes & Noble. It was a coffee table sized book (as they’re called), beautifully bound about a priest in the Church of England, the Reverend Robert Francis Kilvert, whose parish was in Wales, far from London’s maddening crowds, but who lives on while others have been forgotten. Why? Because he left his diary, called by a reviewer in the Guardian of England, “The most enchanting portraits of English rural life ever written.”

He was neither the Archbishop of Canterbury nor Dean of St. Paul’s, but a lowly priest in far off Wales, who died when he was 39, but he told us about his life and that of others and provided an invaluable look about a period of which too little is known.

I will end with one of my greatest heroes, Samuel Johnson, who gave us the incomparable gift of the first English dictionary, as stunning an achievement as any ever in the English-speaking world.

In Dr. Johnson’s first volume of his dictionary, A through K, there are about 24,000 quotations from the English poets, 8,500 from Shakespeare, 5,600 from Dryden, 2,700 from Milton, and more than 10,000 from philosophers, 1,600 from John Locke, and 5,000 from religious writers.

The two volumes of the dictionary contain more than 116,000 quotations – more than twice of which came from the great man’s memory.

Dr. Johnson had sought the financial assistance of Lord Chesterfield in his undertaking of composing the dictionary, which had not always gone well, causing him to write this famous letter:

“Seven years, my Lord, have now passed since I waited in your outward rooms or was repulsed from your door…

“Is not a patron, my Lord, one who looks with unconcern on a man struggling for life in the water and when he has reached ground encumbers him with help? The notice which you have been pleased to take of my labors, had it been early, had been kind; but it has been delayed till I am indifferent and cannot enjoy it, till I am solitary and cannot impart it, till I am known and do not want it.

“I hope it is no very cynical asperity not to confess obligations where no benefit has been received, or to be unwilling that the public should consider me as owing that to a patron, which Providence has enabled me to do for myself.”

I hope for you a memorable May.

George Mitrovich is a San Diego civic leader. He may be reached at gmitro35@gmail.com.

Category: Education, feature, Local News, National News